Two people look enough alike that one could pass for the other. Can they pass? What happens when people mistake you for someone else? What would you need to know in order to fit yourself into someone else’s life?

Two people look enough alike that one could pass for the other. Can they pass? What happens when people mistake you for someone else? What would you need to know in order to fit yourself into someone else’s life?

Authors have played with this idea for centuries. There are the separated twins in Roman playwright Plautus’s The Two Menaechmuses, Shakespeare’s A Comedy of Errors and Twelfth Night, and Dumas’ The Man in the Iron Mask (~1850); the distant relations who look identical in Anthony Hope’s The Prisoner of Zenda (1894); the similar or identical strangers in Dumas’ The Two Dianas (1846, which borrows the real-life case of Martin Guerre), Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities (1859), Twain’s The Prince and the Pauper (1881), E. Phillips Oppenheim’s The Great Impersonation (1920), Jane Lewis’s The Wife of Martin Guerre (1941), and Josephine Tey’s Brat Farrar (1949); and the device of actually switching bodies in Thomas Anstey Guthrie’s Vice Versa (1882).

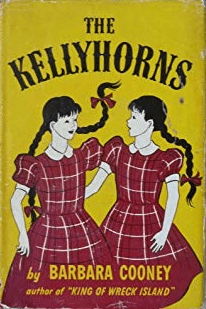

Switching places burst onto the scene of children’s books in 1942 with The Kellyhorns by Barbara Cooney. Twin girls are separated in infancy because of the death of their mother, one staying with the father, the other going to an aunt. Because of a family estrangement, the two girls have never met. When they do meet, they switch places in order to facilitate bringing together the father and the aunt, who were sweethearts long ago.

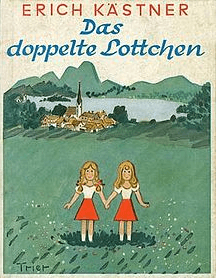

Does this sound familiar? Yes, it bears an uncanny resemblance to the movie The Parent Trap (1961), which was based on the German book Das Doppelte Lottchen (1949, English title Lottie and Lisa), by Erich Kästner. Kästner first proposed his idea in 1942, the year The Kellyhorns was published.

Does this sound familiar? Yes, it bears an uncanny resemblance to the movie The Parent Trap (1961), which was based on the German book Das Doppelte Lottchen (1949, English title Lottie and Lisa), by Erich Kästner. Kästner first proposed his idea in 1942, the year The Kellyhorns was published.

In The Kellyhorns, Pamela is raised by Aunt Ivory, a disappointed spinster whose greatest joy in life is winning the quilting competition at the county fair. Penny is raised by Barnabas Kellyhorn, the girls’ “Puppa.” They live a few towns over from Ivory and Pamela, on a small island in the bay.

Once the two girls have connected, they hatch their plot to bring Ivory and Barnabas together, but first they have to make sure they will each like the other parent. On a visit, they simply swap clothes and redo their hair, and Penny goes home to Aunt Ivory, while Pam stays with Barnabas. Penny has to get used to Pam’s pink-and-white bedroom, her dresses, Aunt Ivory’s rules. Pam has to get used to wearing overalls and climbing a rope ladder to her attic bedroom. Penny is helped by Pam’s best friend, who is in on the secret, and likewise Pam is helped by Penny’s cousin-and-adoptive-brother Barney. Neighbors have to be memorized in a hurry, as well as a map of the town, and each girl has to deal with being better and worse in different school subjects than the other. This book digs a lot of fun out of the hazards of faking an identity. It’s a puzzle why books that use this premise so often don’t do it full justice.

There’s a lot more to The Kellyhorns as well. Aunt Ivory may seem prim, but she is fully capable of pulling a revolver on a bad guy, and before she settles down with Barnabas she fulfills her life-long dream of running away to join the circus. Then there is the bad guy, Rusty Hanna, a disreputable drunk who is cruel to animals and whose role in the story is rather similar to that of Injun Joe in Tom Sawyer. (My daughter confused them for a while, referring to both characters as “Rusty Engine.”) His vendetta against the Kellyhorn family, begun when Aunt Ivory refuses to give back his mistreated cat, leads to a highly dramatic climax. Even after the twins’ ruse is over, their identical looks figure in the resolution of the plot. There are also numerous sub-plots, deftly woven together, including finding out where Aunt Ivory ran away to, Barnabas reconnecting with his long-absent brother, a beloved member of the community framed for a crime committed by Rusty Hanna, and two old people finding love.

Since The Kellyhorns, numerous children’s books have used this switched-identities plot device. The aforementioned Lottie and Lisa and The Horse and His Boy (C.S. Lewis, 1954) use twins separated at birth. Devices such as time travel, in Jessamy (Barbara Sleigh, 1967) and Charlotte Sometimes (Penelope Farmer, 1969), or witchcraft, in Charmed Life (Diana Wynne Jones, 1977), replace one child with another, requiring them to fake an identity with very little to go on. Freaky Friday (Mary Rodgers, 1972) re-uses the concept of Vice Versa, with a daughter and her mother switching bodies. Father’s Arcane Daughter (E.L. Konigsberg, 1976) takes more of the Martin Guerre approach, in which a person resembling a long-missing family member turns up, having first pumped background knowledge from an informant.

Since The Kellyhorns, numerous children’s books have used this switched-identities plot device. The aforementioned Lottie and Lisa and The Horse and His Boy (C.S. Lewis, 1954) use twins separated at birth. Devices such as time travel, in Jessamy (Barbara Sleigh, 1967) and Charlotte Sometimes (Penelope Farmer, 1969), or witchcraft, in Charmed Life (Diana Wynne Jones, 1977), replace one child with another, requiring them to fake an identity with very little to go on. Freaky Friday (Mary Rodgers, 1972) re-uses the concept of Vice Versa, with a daughter and her mother switching bodies. Father’s Arcane Daughter (E.L. Konigsberg, 1976) takes more of the Martin Guerre approach, in which a person resembling a long-missing family member turns up, having first pumped background knowledge from an informant.