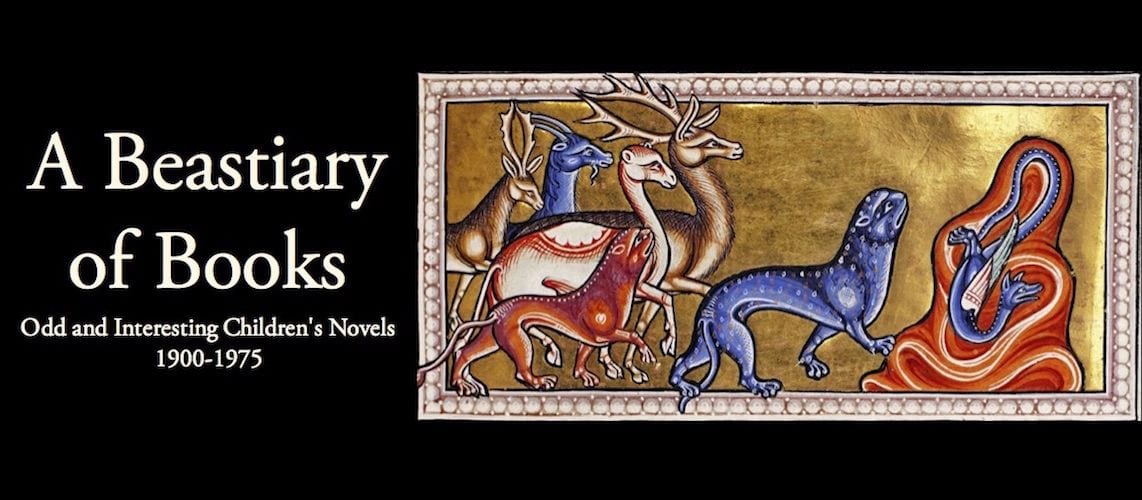

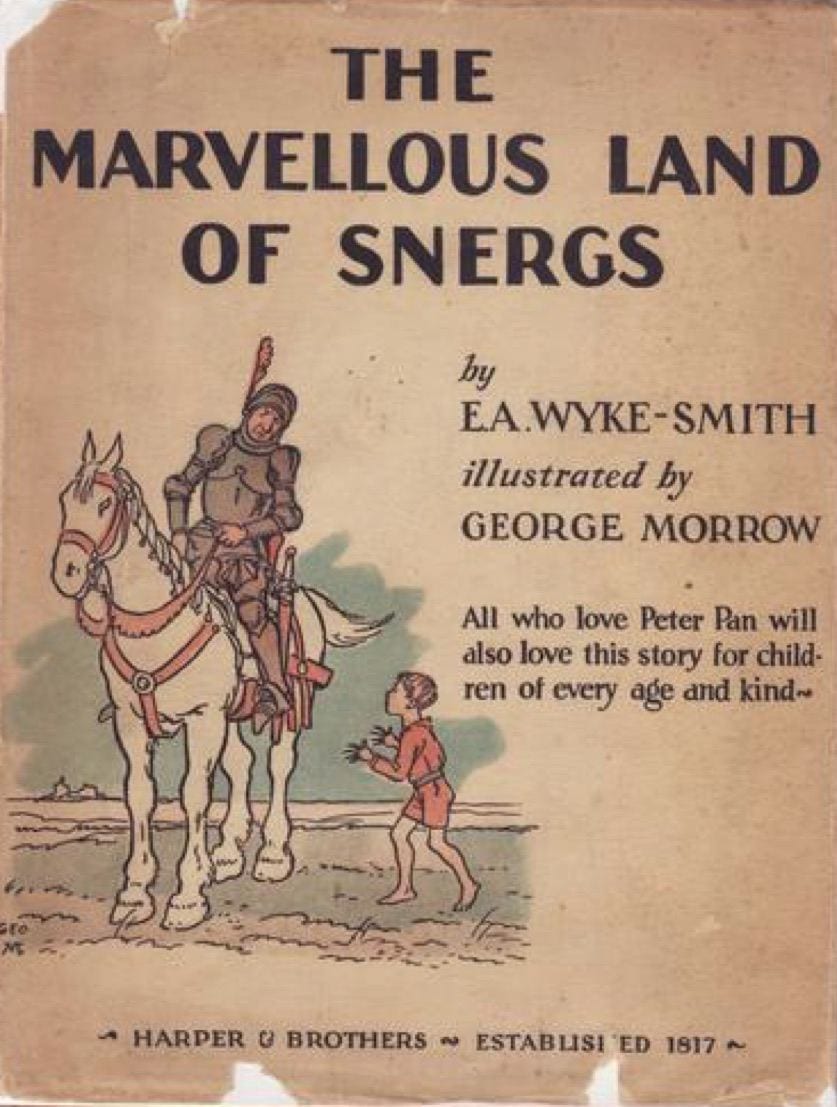

The S.R.S.C. (Society for the Removal of Superfluous Children) has established a colony for children unwanted by their parents, at Watkyns Bay which cannot be reached from the ordinary world unless you know how. (The one exception is a cursed boatful of 17th century Dutch sailors.) There, the children live a life of play and adventure, between the woods and the seaside, in a land reminiscent of Peter Pan without the creep factor. Two of the children, Sylvia and Joe, are caught making mischief, and run away from Watkyns Bay to the nearby land of the Snergs. Adventures ensue, with an ogre, a witch, a jester, a rumored tyrant king who turns out to be benevolent, and the faithful companionship of a Snerg named Gorbo. After the Dutchmen and Snergs stage a rescue operation, Sylvia and Joe are safe again.

The S.R.S.C. (Society for the Removal of Superfluous Children) has established a colony for children unwanted by their parents, at Watkyns Bay which cannot be reached from the ordinary world unless you know how. (The one exception is a cursed boatful of 17th century Dutch sailors.) There, the children live a life of play and adventure, between the woods and the seaside, in a land reminiscent of Peter Pan without the creep factor. Two of the children, Sylvia and Joe, are caught making mischief, and run away from Watkyns Bay to the nearby land of the Snergs. Adventures ensue, with an ogre, a witch, a jester, a rumored tyrant king who turns out to be benevolent, and the faithful companionship of a Snerg named Gorbo. After the Dutchmen and Snergs stage a rescue operation, Sylvia and Joe are safe again.

Much of the charm of the book is in the beginning. We learn about the cinnamon bears that live in the woods, whose soft fur smells slightly of cinnamon, and who try to get into the houses at night, making the children giggle. The Snergs do much of the daily work for the S.R.S.C.: “When they are bathing a Snerg or two sits on a rock ready to dive in and pick out any child that has got into trouble. It is interesting to see how they reach such a one with a few vigorous strokes, take it to land, up-end it by the heels to let the water run out, and lay it on the grass to dry.”

Unfortunately, the middle sags badly, and for a while we seem trapped in a nonsense book. There are even giant edible mushrooms, as per Alice and The Magical Land of Noom, and an ogre with a conscience (or so we think) like the Hungry Tiger of the Oz books. The ending is saved, though, by a return of the author’s distinctive style. Here is the king mourning Baldry the Jester, who is pretending to be dead: “‘Too late poor fool, this unavailing woe! I loved thee more than thou did’st ever know.’ ‘Then in that case,’ said Baldry, turning smartly onto his back, ‘why are you making things so difficult?'”

Be aware that violence, though rare, is shockingly frank. Near the beginning, there is a too-realistic description of keel-hauling. Later in the book, the villains meet gruesome ends, but a certain sort of child will find this funny. “‘Yes,’ agreed King Merse as he looked, ‘it is undoubtedly as you say. That is Mother Meldrum–or part of her.'” The author concludes that the moral of his tale is, “if you by any chance meet an ogre who claims to be reformed, pretend to believe him until you have got a gun and then blow his head off at the first opportunity.”

Though now forgotten, Snergs was influential in its day. Snergs‘s Miss Watkyns, founder of the S.R.S.C., would appear to be the original for Mary Poppins (1934), stepping in with a stiff exterior to care for and entertain children. They even look the same, down to the sensible shoes. She and the other ladies depart for Watkyns Bay by meeting “on Hampstead Heath one blowy October night.” When all the ladies (each with one well-wrapped superfluous child) have gathered, “she gave the word and away they all went on a high wind.”

Tolkien openly acknowledged the impact of Snergs on The Hobbit (1938). Hobbits resemble Snergs in being short and fond of feasting, and in living a very long time with a prolonged childhood and youth. (Snergs, in their turn, may have been based on the Munchkins, Winkies, Gillikins, and Quadlings of Oz. It was at any rate an unsavory fashion of the time to use a real variant of the human form as the basis for a humorous and childlike “race” of not-quite-humans.) Then there is the matter of naming, with Gorbo clearly in the same vein as Bilbo and Frodo (along with dozens of other hobbits with -o names, like Bungo and Minto and Dudo). This may have been part of a larger cultural trend of -o endings, including Jumbo the elephant, the invention of the game Bingo, and the names of the Marx Brothers.

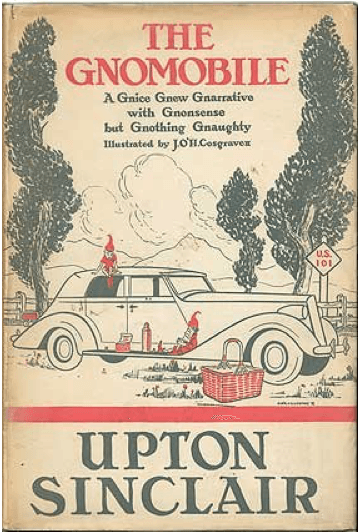

But slightly before The Hobbit, another author copied these features of the snergs. In 1936, Upton Sinclair published The Gnomobile. The gnomes in this book are named Bobo and Glogo, and are respectively a youthful 100 years old and a venerable 1,000.

But slightly before The Hobbit, another author copied these features of the snergs. In 1936, Upton Sinclair published The Gnomobile. The gnomes in this book are named Bobo and Glogo, and are respectively a youthful 100 years old and a venerable 1,000.