The movie of The Rescuers has almost nothing to do with the book, but even if you read the book and it’s sequels as a child, you may not realize how weird it is. It is not even a book for children. It’s a Ruritanian romance, with mice.

The movie of The Rescuers has almost nothing to do with the book, but even if you read the book and it’s sequels as a child, you may not realize how weird it is. It is not even a book for children. It’s a Ruritanian romance, with mice.

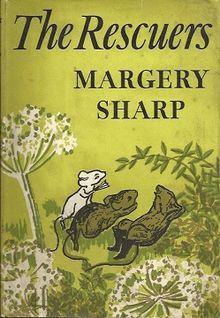

Ruritanian romances were a style of swashbuckler typified by The Prisoner of Zenda (whose fictional Ruritania gave the genre its name). They were generally set in small fictional central European or Balkan countries. They involved modern-day (as of the late Victorian era) royalty caught up in political intrigue, and romance thwarted by the neccessities of honor.

In The Prisoner of Zenda, the handsome young king is being plotted against by his evil half-brother the duke, who drugs him so that he will not be present at his coronation. The king’s loyal advisers meet his distant cousin who happens to be his exact double. They talk the cousin into taking the king’s place, saving the country from falling into the hands of the wicked duke. Unfortunately the cousin falls in love with the king’s fiancee, a love they must renounce for the greater good. There is also a dashing rescue of the real king from the fortress castle where he is imprisoned. All this nicely sums up the key elements of Ruritanian romance. The genre has also been satirized plenty, in books as diverse as The Mouse that Roared and The Princess Bride. And The Rescuers.

In The Prisoner of Zenda, the handsome young king is being plotted against by his evil half-brother the duke, who drugs him so that he will not be present at his coronation. The king’s loyal advisers meet his distant cousin who happens to be his exact double. They talk the cousin into taking the king’s place, saving the country from falling into the hands of the wicked duke. Unfortunately the cousin falls in love with the king’s fiancee, a love they must renounce for the greater good. There is also a dashing rescue of the real king from the fortress castle where he is imprisoned. All this nicely sums up the key elements of Ruritanian romance. The genre has also been satirized plenty, in books as diverse as The Mouse that Roared and The Princess Bride. And The Rescuers.

In The Rescuers, three mice set out to rescue a prisoner, a Norwegian poet being held in an impenetrable Balkan fortress. The trio comprises the cultured, elegant Miss Bianca who is the pet of a diplomat’s son; the rough, stalwart Bernard, who is tongue-tied in Miss Biana’s presence but nevertheless makes her heart flutter; and their sea-faring Norwegian translator Nils. After an arduous journey, and many dangers involving jailers and cats, they locate the poet in his grim dungeon and help him to escape. In the end, Miss Bianca regretfully gives up her chance to stay with Bernard because her place is with the diplomat’s son. The book bristles with irony and wit, and is very Ruritanian.

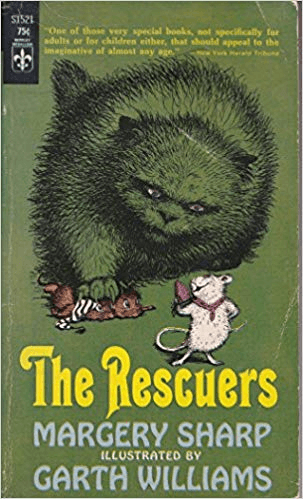

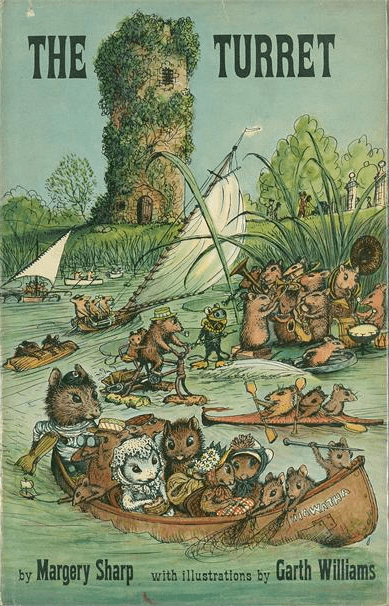

Someone in marketing must have decided to flip this to the children’s side (because: talking animals!), assisted by the fluffier drawings of Garth Williams for the American edition. (Though even the first couple of American editions still appear to have been aimed at adults. The green one was a pocket edition with small print. But eventually it got tossed over to Yearling, with full-on cute.) Sharp subsequently churned out endless child-aimed sequels. Miss Bianca and Bernard end up as pals with a kind of low-key crush on each other.

Someone in marketing must have decided to flip this to the children’s side (because: talking animals!), assisted by the fluffier drawings of Garth Williams for the American edition. (Though even the first couple of American editions still appear to have been aimed at adults. The green one was a pocket edition with small print. But eventually it got tossed over to Yearling, with full-on cute.) Sharp subsequently churned out endless child-aimed sequels. Miss Bianca and Bernard end up as pals with a kind of low-key crush on each other.

That said, children’s literature does seem to have an affinity for Ruritanian romance, minus some of the more convoluted politics and the kissing. Children’s books that draw on elements of the genre include The Prince Commands by Andre Norton, The Twilight of Magic by Hugh Lofting, The Chestry Oak by Kate Seredy (who also illustrated The Prince Commands), and the Tintin comic book King Ottokar’s Scepter. An adult Ruritanian romance, The Lost Prince, was written by France Hodgson Burnett, author of A Little Princess and The Secret Garden.