A class of French fifth-graders during the German occupation have been evacuated to the countryside, where a nun runs a school in an old house. The story begins with a stunningly good bit of action: the children are playing make-believe, and this being a Catholic culture and just past Christmas, the flight of Jesus’s family to Egypt is a natural choice. But as soon as they start playing, the children begin to incorporate everyday realities. Mary and Joseph are Displaced Persons. How will they get food? They have no ration cards. And so on.

Then almost immediately, things get real. The teacher calls them into the classroom, where they learn that ten Jewish children need a place to hide. The children agree to take them in and keep this dangerous secret. The stakes get suddenly higher when German soldiers arrive while the teacher is away. Together the children collaborate on a plan: the ten Jewish children hide in a cave, and the twenty Christian children play dumb and refuse to speak to the soldiers. The eventual resolution is both funny and earnest, when the children make fools of the soldiers by claiming that three of them are the Jews: Jesus, Mary, and Joseph, as they had been playing in their game.

Many, many children’s books have been written about WWII. Some are moralistic. Some are determined to educate children about history. This one stands out of the pack because Bishop herself was French, and she knew the people and the place she was writing about. There are small, telling details, such as that men from the Normandy region were clean-shaven “like Americans” (and we infer that most Frenchmen were not). Bishop even sneaks in a mention of L’Heure Joyeuse, the children’s library that she herself founded in Paris. Though she moved to the U.S. in the 1930’s and made a career at the New York Public Library, she was accutely aware of conditions in her homeland. As the story unfolds, we learn details such as how precious a single square of chocolate was, and how a fresh orange was even more exciting than chocolate. How even children who were basically safe and healthy during the war never quite got enough to eat. Bishop was a Catholic who was a lifelong advocate of religious cooperation and a vocal opponent of anti-semitism within the Catholic church. The book is earnest, even moral, in tone, but it is not santimonious. Futhermore, the story she tells here is based on a real event. The reader doesn’t need to know this, to sense the slightly-not-quite-what-you-expected quality of authorial honesty.

Many, many children’s books have been written about WWII. Some are moralistic. Some are determined to educate children about history. This one stands out of the pack because Bishop herself was French, and she knew the people and the place she was writing about. There are small, telling details, such as that men from the Normandy region were clean-shaven “like Americans” (and we infer that most Frenchmen were not). Bishop even sneaks in a mention of L’Heure Joyeuse, the children’s library that she herself founded in Paris. Though she moved to the U.S. in the 1930’s and made a career at the New York Public Library, she was accutely aware of conditions in her homeland. As the story unfolds, we learn details such as how precious a single square of chocolate was, and how a fresh orange was even more exciting than chocolate. How even children who were basically safe and healthy during the war never quite got enough to eat. Bishop was a Catholic who was a lifelong advocate of religious cooperation and a vocal opponent of anti-semitism within the Catholic church. The book is earnest, even moral, in tone, but it is not santimonious. Futhermore, the story she tells here is based on a real event. The reader doesn’t need to know this, to sense the slightly-not-quite-what-you-expected quality of authorial honesty.

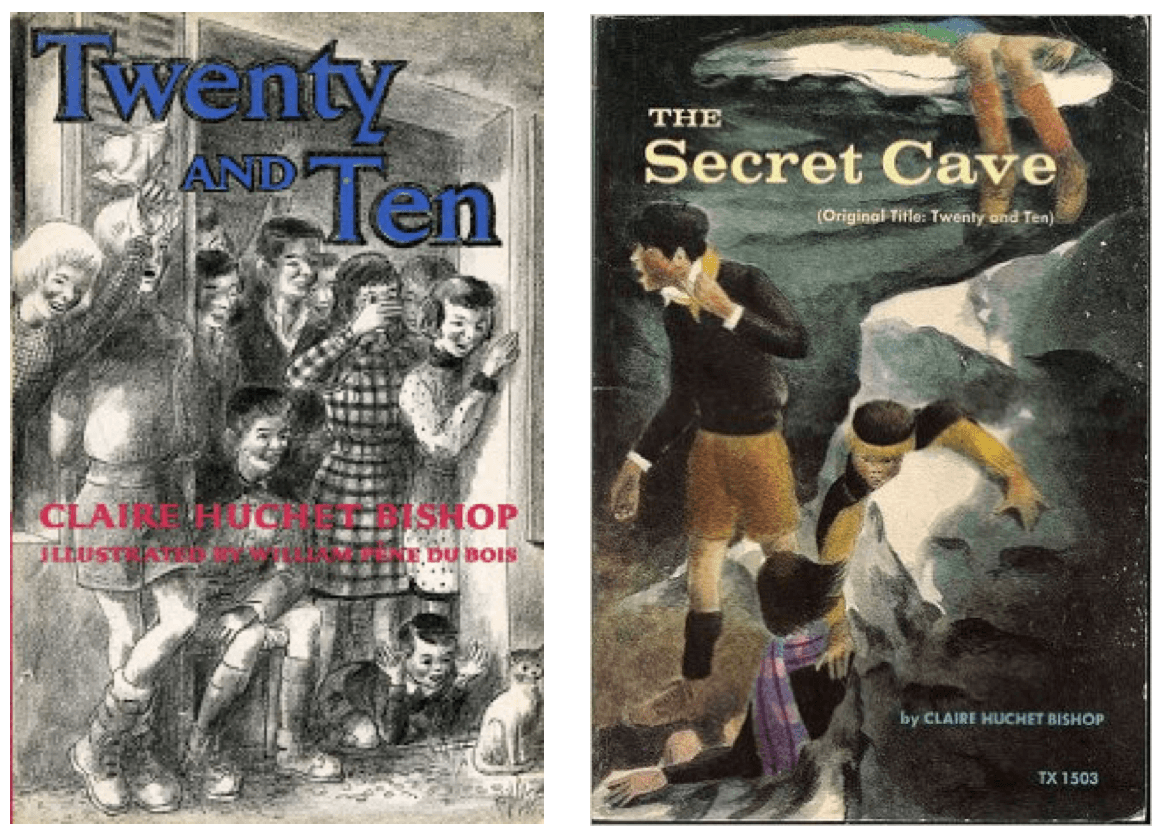

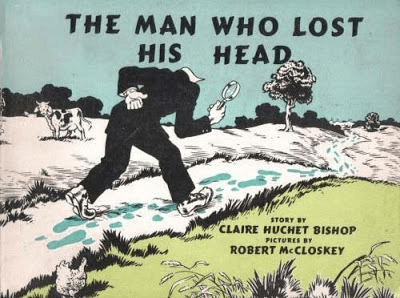

Bishop wrote many other books, some of which are rather a surprise: the classic but now desperately dated The Five Chinese Brothers (1938); and The Man Who Lost His Head (1942), illustrated by Robert McCloskey of Make Way for Ducklings fame, whose distinctive style doesn’t even belong in the same universe as Twenty and Ten. Twenty and Ten itself was illustrated by William Pene Du Bois (author of The Twenty One Balloons).

Bishop wrote many other books, some of which are rather a surprise: the classic but now desperately dated The Five Chinese Brothers (1938); and The Man Who Lost His Head (1942), illustrated by Robert McCloskey of Make Way for Ducklings fame, whose distinctive style doesn’t even belong in the same universe as Twenty and Ten. Twenty and Ten itself was illustrated by William Pene Du Bois (author of The Twenty One Balloons).