As I mentioned in my last post, E. Nesbit was probably the single most influential children’s author of the early 20th century. Other authors, like L. Frank Baum, may be more widely known today, but there’s really not much lasting imprint of Oz on children’s literature. E. Nesbit, on the other hand, is everywhere. In later posts, I’ll be getting into some of the themes and variations of Nesbit that echoed through the entire 20th century. Here we’ll talk a bit about Nesbit herself.

As I mentioned in my last post, E. Nesbit was probably the single most influential children’s author of the early 20th century. Other authors, like L. Frank Baum, may be more widely known today, but there’s really not much lasting imprint of Oz on children’s literature. E. Nesbit, on the other hand, is everywhere. In later posts, I’ll be getting into some of the themes and variations of Nesbit that echoed through the entire 20th century. Here we’ll talk a bit about Nesbit herself.

E. Nesbit didn’t emerge ex nihilo, of course. She was part of the ongoing flow of children’s fiction from the Victorian era, and its influences on her should not be underestimated. She was steeped in the fairy stories and the boys’ adventure stories of the previous century, and she was not above using sentimental Victorian tropes to tie a story together. (She had a particular weakness for loved ones parted by cruel fate, then reunited by splendidly ridiculous coincidence.)

Less obviously, she also drew on ideas in adult fiction that had not yet made it into children’s literature. This was a time when stories about fantasy worlds, the supernatural, time travel, and science fiction were in their nascent form and still being eplored as terra incognita, not yet relegated to genre fiction.

Her genius, though, was in combining these elements using an alchemy of her own to create something fresh. Among her innovations: creating living, breathing child characters, with all their foibles and personality quirks; crossing gender lines in her appeal (usually with a carefully balanced set of two girls and two boys); bringing magic into the everyday world; challenging her readers with witty writing and sly social commentary; and tapping into children’s real, fervent imaginings (“What if I could go back to ancient Egypt? What if this toy city I just built were real?”) We take all these things for granted today.

So should modern children try to read Nesbit’s books? As always, it depends on the child, their interests, and what they have patience for. But here are some general considerations.

First, to get into the groove of E. Nesbit, it’s important to know that her books were serialized in magazines, and it shows in their structure (or lack thereof). Many of her books are straight-up episodic, such as Five Children and It, meant to be read almost as stand-alone stories. Others of her books are more planned, but have an odd slithery quality that show the writer’s ideas shifting over time, such as The House of Arden. Her later books, such as The Enchanted Castle, when she had had some practice wrestling with this problem, are fairly well constructed, but the pressure of “how shall I entertain them this week” can still be felt. Modern readers just need to learn to roll with the serialized novel.

First, to get into the groove of E. Nesbit, it’s important to know that her books were serialized in magazines, and it shows in their structure (or lack thereof). Many of her books are straight-up episodic, such as Five Children and It, meant to be read almost as stand-alone stories. Others of her books are more planned, but have an odd slithery quality that show the writer’s ideas shifting over time, such as The House of Arden. Her later books, such as The Enchanted Castle, when she had had some practice wrestling with this problem, are fairly well constructed, but the pressure of “how shall I entertain them this week” can still be felt. Modern readers just need to learn to roll with the serialized novel.

Next is the difficulty of getting comfortable in Edwardian English culture. A lot of time has passed, and things have changed. In Nesbit’s world, relations between children and adults were often cold and adversarial, which will probably bother the modern child a great deal more than it bothered Nesbit’s characters. (Nesbit’s characters generally have warm relationships with their parents, but spend far more time interacting with grouchy cooks and the like.) Cultural references, household habits, brand-names and more have all changed. Nesbit books are best read with a computer search engine handy and a grown up who can help to speculate about the obscure references. Assumptions about social class can also be disconcerting. Nesbit’s children are generally described as being somewhat poor, by which it is meant that their fathers have to do white-collar work for a living and the children don’t get to go on as many holidays as they would like, though the family can still can afford servants. (Being able to afford only one “general” housemaid/cook meant one was very poor indeed.)

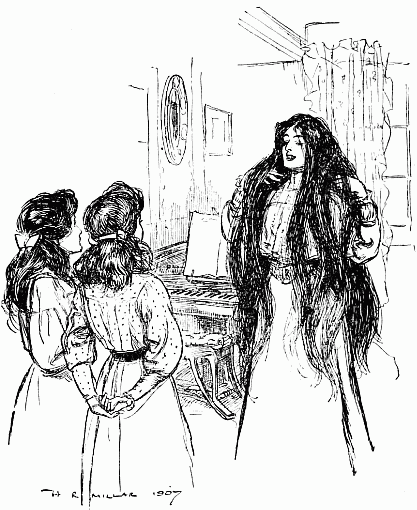

Then there’s the problem of illustrations. I’m usually a purist for original illustrations, but H.R. Millar, who illustrated almost all of E. Nesbit’s works, had a harsh scratchy quality that worsens the difficulties of a modern child trying to get comfortable in E. Nesbit’s world (and it doesn’t help that modern reproductions are often bad quality). It’s a shame, because this was the era of Art Nouveau, as well as the Golden Age of Illustration, when so much gorgeous book-illustrating was being done. There is, unfortunately, no one best replacement illustrator.

Finally, there is the problem of the racism and classism endemic in Nesbit’s books. (It’s odd, because Nesbit was a socialist and political activist, themes which she occasionally makes explicit in her books. But there you are.) Nesbit was a social satirist, and the danger with social satire is that it mocks people without trying to understand why they are the way they are. For this reason, the principle of “punch up, not down” is particularly important in satire. But Nesbit was an equal opportunity satirist, and along with bankers and law-makers and newpaper publishers and grownups who boss children around, she also mocks servants, working-class people in general, Jews, Romani, and non-European people of all sorts. (It should also be said that Millar’s drawings of tribal cultures are not just racist in an uninformed or patronizing way, they are viciously hateful.)

Some of this can be fixed with judicious skipping, if you’re reading aloud. (I’m not opposed to taking an axe to The Phoenix and the Carpet, ditching both of the visits to the “cannibal” island, including the entire lead-up to the second visit with the persian cats and the cow and the burglar, none of which is very interesting.) But since Nesbit will probably only appeal to older readers anyway, the best answer is to discuss, discuss, discuss.