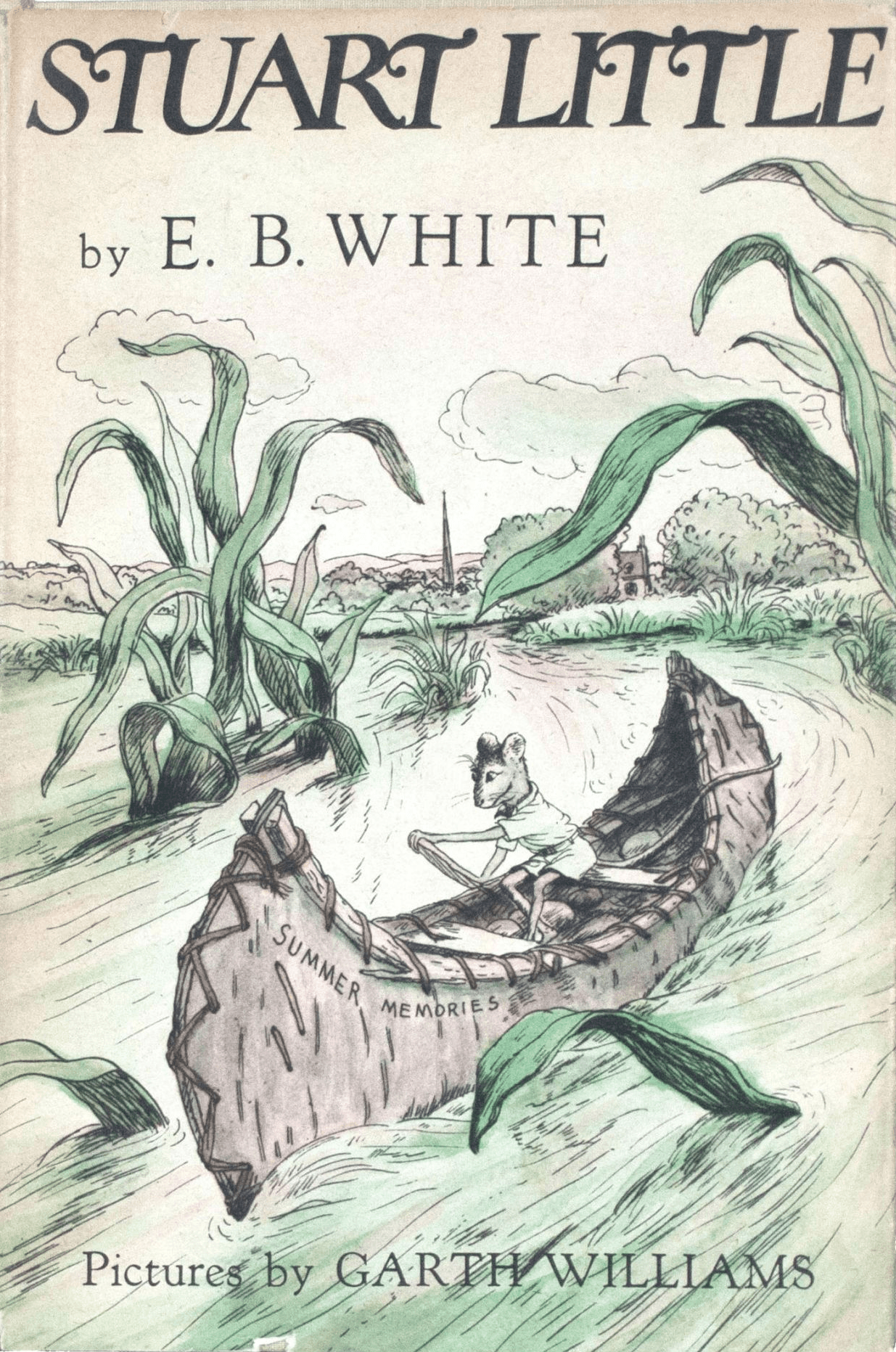

Though I be beaten to death by enraged fifth-grade teachers, I have to say it: Stuart Little is a terrible book.

Though I be beaten to death by enraged fifth-grade teachers, I have to say it: Stuart Little is a terrible book.

First off, the premise — that Mrs. Little gave birth to a mouse — just doesn’t bear thinking about. But we’ll let that pass; we’ll pretend that White’s target audience in the 1940’s knew nothing about the facts of life.

More important, what is this book even about?

The first half is Stuart living life as a very small person, with clever uses of ordinary objects, like a cigar box held up by clothespins for a bed, and including a long interlude of Stuart sailing a toy boat on the pond in Central Park. (This kind of territory was already explored a bit by children’s novels like Ben and Me,1939, and The Little Grey Men, 1942, which incidentally includes the characters making use of a toy boat. But to give credit where it is due, Stuart Little was the first children’s novel to really explore the charms of this kind of thing. It has been taken up since by books like The Borrowers, 1952; The Rescuers, 1959; and The Littles, 1967.)

Then Stuart befriends a bird, and after a few more minor adventures the bird flies north and Stuart decides to follow, in a toy automobile. The second half of the book is about his adventures on the road, and we are given to understand that it is not just about finding the bird but about some ineffable longing of the soul.

Stuart takes a gig as a substitute teacher in a small town (the Superintendent of Schools is weirdly sitting by the side of the road depressed that he can’t find a substitute), which gives E.B. White a chance to display his contempt for modern education methods. White also has extremely bizarre ideas about how school children talk and think. One of them, when asked what’s important, says, “A shaft of sunlight at the end of a dark afternoon, a note in music, and the way the back of a baby’s neck smells if its mother keeps it tidy.” If this isn’t an author manipulating his characters to make his own point, I don’t know what is.

In another town Stuart has a brief flirtation with a human teenage girl his own size (and again may I say, ew), but it doesn’t work out because his plans for showing off to her on their date get ruined and he’s not willing to consider doing anything else fun with her. So Stuart goes on his way.

And the book ends.

Rumor has it that White rushed the ending because he was worried about his health, but generations of adults have persisted in believing this is somehow profound.

First up, it’s not a terrible book. But only if you accept that it’s not a kids’ book neither.

This despite my copy – which your column prompted me to re-read – being given to me when I was 9 months old. East-coast academics really have high expectations for their friend’s kids!

The first chapters are sort of coherent, if you read them as an absurdist or surrealist piece. Is being accepted as a humanoid mouse any different from awaking one day as an insect? Or is it some metaphor for the the extended struggle of the little man in the big city? The eloquent schoolkids are no less surreal than the angelic talking bird or the 2- inch tall girl. Maybe the malevolent cat represents the impersonal, plausible capitalists who really are out to get you.

And then the date with the tiny, perfect woman. There’s a beautiful description of an anxiety attack in that chapter, changing his sweat-soaked shirt on the hour every hour. So it’s perfectly consistent that when everything does fail so catastrophically, the only thing left to do is jump in the car and drive away. towards the far horizon.

So no, not a kids book.