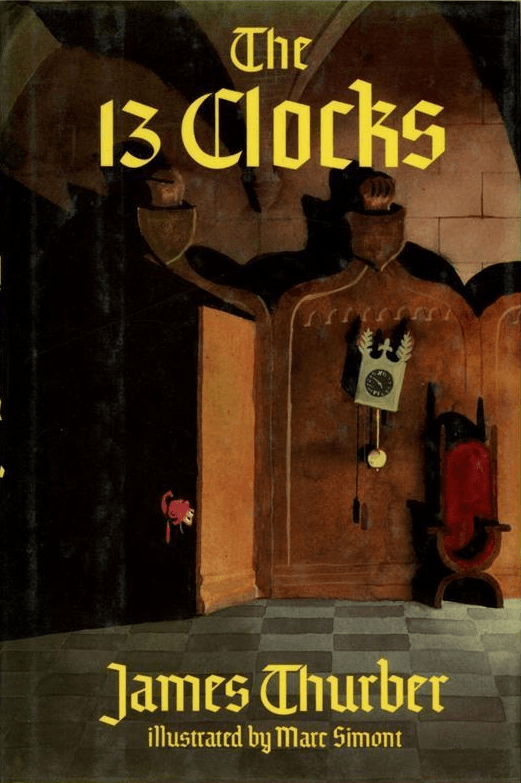

I cannot do better than to quote from the front flap:

I cannot do better than to quote from the front flap:

How can anyone describe this book? It isn’t a parable, a fairy story or a poem, but rather a mixture of all three. It is beautiful and it is comic. It is philosophical and it is cheery.

There are only a few reasons why everybody has always wanted to read this kind of a story, but they are basic: Everybody has always wanted to love a Princess. Everybody has always wanted to be a Prince. Everybody has always wanted the wicked Duke to be punished.

Too little of this kind of thing is going on in the world today. But all of it is going on valorously in The Thirteen Clocks.

(This “everybody” is pretty accurate, if we ignore the gender markers. Everyone wants to be dashing and admirable, and be loved for it. Harder to reconcile is the story itself, in which the princess is a passive prize to be won. There’s no fix for this, so save this book for a child old enough to understand the concept of liking something in-spite-of.)

The story, briefly, is this: a prince wandering in disguise comes to an island ruled by a wicked Duke, who is holding a princess under a spell. Other princes have tried to rescue her and failed. Our prince, however, is aided by the Gollux, a diminutive and unreliable guide who turns out to make all the difference. Together they travel to find a thousand jewels, release the princess from her spell, and leave the Duke to be eaten by the Todal, a creature who punishes evil-doers for not being evil enough.

But how can a plot summary do justice to a book in which almost every line is quotable? It’s easily missed even after a dozen readings, but Thurber was loosely writing in iambic pentameter, which gives the book a heroic feel without the reader being entirely sure how. The details are hilarious and touching, from the Gollux’s indescribable hat, to the thirteen frozen clocks that must be started to bring Now back to the castle, and from the Duke’s habit of feeding his varlets to the geese, to the purple ball stamped with gold stars that bounces down the stairs “like a naked child saluting priests.” The story bristles with literary allusions: Shakespeare, Sherlock Holmes, Greek drama, fairy tales, Errol Flynn movies, Arthurian romances, “Ruritanian” romances. The rose that the princess gives the prince to guide him is, if you think about it, a compass-rose. And . . .

But how can a plot summary do justice to a book in which almost every line is quotable? It’s easily missed even after a dozen readings, but Thurber was loosely writing in iambic pentameter, which gives the book a heroic feel without the reader being entirely sure how. The details are hilarious and touching, from the Gollux’s indescribable hat, to the thirteen frozen clocks that must be started to bring Now back to the castle, and from the Duke’s habit of feeding his varlets to the geese, to the purple ball stamped with gold stars that bounces down the stairs “like a naked child saluting priests.” The story bristles with literary allusions: Shakespeare, Sherlock Holmes, Greek drama, fairy tales, Errol Flynn movies, Arthurian romances, “Ruritanian” romances. The rose that the princess gives the prince to guide him is, if you think about it, a compass-rose. And . . .

Look, just read it, okay?

Ok! OK! I don’t know how I missed this one, but I will get on it immediatly (as soon as I find it).

And “a wandering minstrel I” from the Mikado…

Thanks for prompting us to re read this! Much better when actually noticing the iambics

Oh, good catch! I forgot that I’d forgotten to put that in!